Our Research

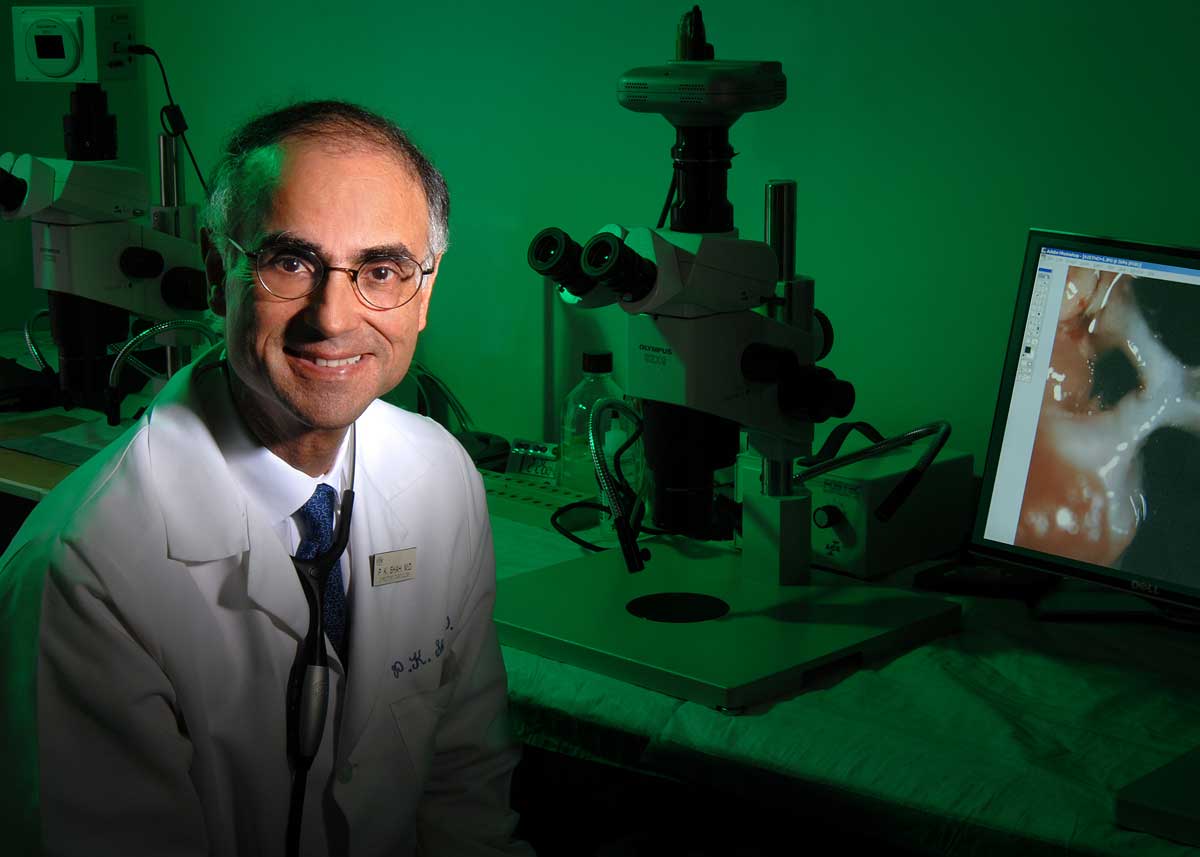

Prediman Krishan (P.K.) Shah, MD

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

- Director, The Helga and Walter Oppenheimer Atherosclerosis Research Center

- Director, Atherosclerosis Prevention and Treatment Center

- Shapell and Webb Family Chair in Clinical Cardiology

- Immediate Past Director, Division of Cardiology

- Director, the Steven S. Cohen Endowed Fellowship in Atherosclerosis Research

Cedars-Sinai and UCLA

- Professor of Medicine and Cardiology

ABOUT DR. SHAH

For P.K. Shah, MD, saving lives is more than a professional vocation – it is also a personal passion. Shortly after he graduated from high school in Kashmir, India, at age 13, his older sister was diagnosed with a rare, rapidly progressive cancer; she died three months later. Dr. Shah has been committed to expanding the boundaries of medical possibility ever since.

It’s a commitment he has leveraged to great effect. As the Shapell and Webb Family Chair in Clinical Cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Dr. Shah sets the standard for superior clinical care and breakthrough research and discovery. His work helps unlock the mysteries of the human heart, transforming patient outcomes by making critical strides in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes and congestive heart failure.

Ranked among the top cardiologists in the country, Dr. Shah is renowned for seeing what lies beyond the scientific horizon. His pioneering research, conducted in collaboration with colleagues around the globe, has paved the way for the development of a vaccine for atherosclerosis and devised a strategy capable of reversing arterial cholesterol buildup. Dr. Shah is quick to credit his success to the people who make it possible: “I derive one of my greatest joys from taking care of patients, and philanthropic support has allowed my research program to thrive.”

After attending medical school in India, Dr. Shah completed three residencies – one in neurology at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi and one in internal medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, before completing a cardiology fellowship at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. In over 35 years as an attending cardiologist with Cedars-Sinai, Dr. Shah has continued to raise the bar on achievement, assuming an extraordinary range of leadership roles including director of inpatient cardiology and the coronary care unit and founder and director of the Helga and Walter Oppenheimer Atherosclerosis Research Center.

Over the course of a truly remarkable career, Dr. Shah’s more than 650 contributions to scientific papers, reviews, book chapters, and abstracts have been prolific and include editing or co-editing four textbooks on heart disease. He has been an active leader of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including Cedars-Sinai’s most prestigious honor, the Pioneer in Medicine Award, as well as the Distinguished Scientist Award from the American College of Cardiology, and the James B. Herrick Award from the American Heart Association.

Dr. Shah is an established visionary in cardiac research, seeing what lies beyond the scientific horizon and uncovering new heart therapies that save countless lives.

RESEARCH PROFILE

Cardiology

P.K. Shah, MD, is on a mission when it comes to matters of the heart. As director of the Cedars-Sinai Smidt Heart Institute’s Oppenheimer Atherosclerosis Research Center and Atherosclerosis Prevention and Treatment Center, and immediate past director of the Division of Cardiology, he leads a team of clinicians and researchers committed to finding next-generation treatments for patients across the globe. His work is revolutionizing the science of cardiac care as it saves countless lives and strengthens the fabric of our community.

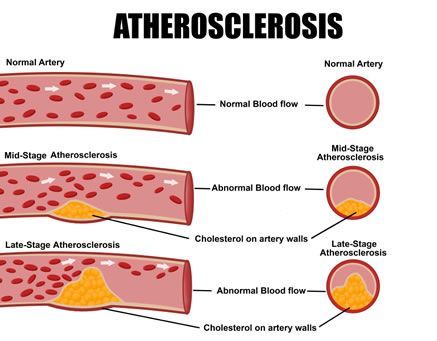

The Power of Protection

What if our bodies could be taught to heal themselves? While studying the population of a small northern Italian town, Dr. Shah discovered that some residents of Limone sul Garda benefit from a mutated gene that provides greater protection against atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation, the processes that lead to clogged arteries, heart attacks, and strokes. This extraordinary finding made international headlines and was featured on CBS’s 60 Minutes in 1994.

Dr. Shah established the Atherosclerosis Research Center in 1993. He is now directing experimental studies showing that the mutated gene produces a protein that can rapidly shrink arterial plaque. Next on the horizon: a technique to deliver the gene itself to the human liver, causing it to start producing the protein on its own. Early results are very encouraging. Dr. Shah and his team are testing the same approach in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease.

Changing the Game

Imagine a vaccine for heart disease that would fend off life-threatening cardiac complications. Working with Swedish scientist Jan Nilsson, MD, PhD, and Cedars-Sinai colleague KY Chyu, MD, Dr. Shah has begun to make this a reality.

Their collaborative efforts have demonstrated the immune system’s capacity to fight against plaque buildup triggered by the LDL (“bad cholesterol”) molecule. The result: the first-ever vaccine for atherosclerosis, engineered from parts of the LDL molecule.

It’s a game-changing development that has been proven to reduce arterial plaque in animal models by 30 to 65 percent. The next step before patient inoculation: human clinical trials.

Ahead of the Curve

Dr. Shah leads the field in uncovering novel approaches to promote and sustain heart health. His many innovations put him ahead of the curve and include conducting the first human study showing how statins reduce the risk of blood clots and demonstrating how to use the electrocardiogram to detect the re-opening of a closed artery at the bedside and without an angiogram.

Committed to expanding the boundaries of medical possibility, Dr. Shah has made critical strides in the treatment of heart disease.

-

1980-1984: USE OF INTRAVENOUS CLOT-DISSOLVING ENZYME TO UNBLOCK ARTERIES REVOLUTIONIZES TREATMENT OF HEART ATTACK PATIENTS

Along with the late William Ganz, MD, describes the use and benefits of intravenous clot-dissolving enzyme to unblock acutely occluded coronary arteries in patients with an acute heart attack, paving the way for a revolution in the treatment of heart attack patients. -

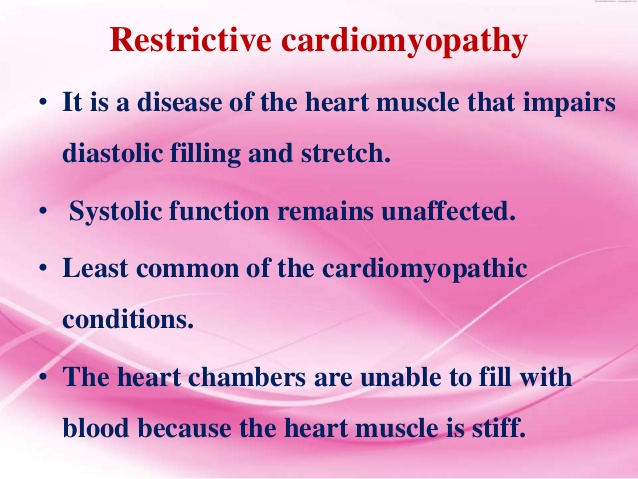

1984: DISCOVERY OF STIFF HEART SYNDROME

Along with colleagues Robert Siegel, MD, and Michael Fishbein, MD, discovers and describes a new disease that causes idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy - stiff heart syndrome. -

1993: NEW BEDSIDE METHOD DEVELOPED TO DETECT THE RE-OPENING OF A CLOSED ARTERY

Describes a new method for using an electrocardiogram (EKG), at the bedside and without an angiogram, to detect the re-opening of a closed artery during clot-dissolving treatment of an acute heart attack. -

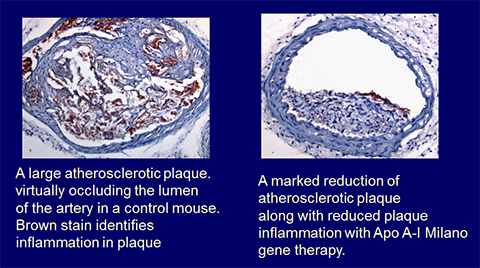

1994: DISCOVERY OF APO A-1 MILANO

Discovers that a genetic mutation in residents of a small Italian town that triggers the production of a key protein - Apo A-1 Milano - may hold a key to natural protection against vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. This leads to the first study showing that intravenous injection of a form of Apo A-1 Milano markedly reduces arterial plaque buildup in animals. The story is told on CBS’s 60 Minutes in 1994. -

1994-2004: PROTECTIVE EFFECTS OF APO A-1 MILANO AGAINST ARTERIAL PLAQUE BUILDUP PROVEN

Reports a series of experimental studies in different animal models showing protective effects of Apo A-1 Milano against arterial plaque buildup, paving the way for a human trial in which these effects were confirmed in 2003. -

1994-Present: DEVELOPMENT OF A VACCINE FOR ATHEROSCLEROSIS USING THE BODY’S OWN IMMUNE SYSTEM

With Swedish scientist Jan Nilsson, MD, PhD, and Cedars-Sinai colleague KY Chyu, MD, identifies that the body’s own immune cells can recognize parts of the LDL (“bad cholesterol”) molecule and help fight arterial plaque buildup. Manipulating the LDL molecule, Shah and Nilsson create a vaccine for atherosclerosis that reduces plaque accumulation in animals by 30 to 65 percent. Human trials of the vaccine are expected to begin soon. -

1995-1999: FIRST STUDY SHOWS THAT OXIDIZED LDL CAN TRIGGER BLOOD CLOTS THAT RESULT IN HEART ATTACK OR STROKE

Conducts the first study showing that oxidized bad cholesterol stimulates white blood cells to produce tissue destructive enzymes. Subsequently oversees the first study illustrating how these enzymes can chew up the protective covering on arterial plaque, triggering blood clots that can result in heart attack or stroke. -

2001: 1ST STUDY DOCUMENTS HOW STATINS REDUCE THE RISK OF BLOOD CLOTS

Directs the first human study documenting how statins that lower bad cholesterol levels work by changing the composition of human carotid artery plaques and reducing the risk of blood clots. -

2001-2004: NEW INSIGHTS INTO THE HUMAN IMMUNE SYSTEM AND PLAQUE BUILDUP

In collaboration with Moshe Arditi, MD, conducts the first-ever study demonstrating that proteins associated with the body’s innate immune system are present in human and animal atherosclerotic plaques, providing new insights into the immune system and plaque buildup. -

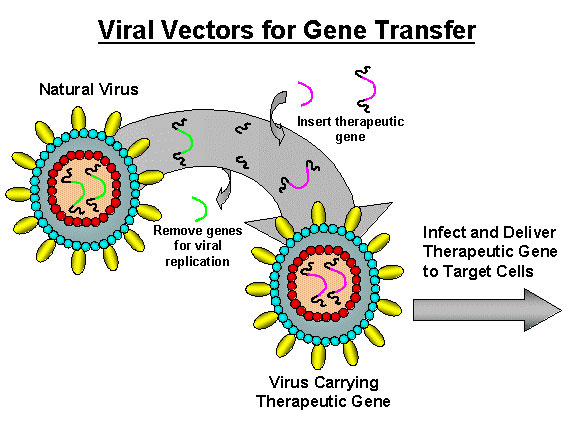

2003-2009: SUCCESSFUL TRANSFER OF APO A-1 MILANO GENE

Reports the successful transfer of the Apo A-1 Milano gene itself, using an innocuous virus as a carrier, into a mouse model, enabling the mouse to manufacture its own supply of the valuable protein. Reports the dramatic benefits of this gene transfer in reducing arterial plaque in animals. Human studies are being planned. -

2006: PLEIOTROPHIN TRANSFORMS WHITE BLOOD CELL INTO A NEW BLOOD-VESSEL-FORMING CELL

Leads the first study revealing that a type of white blood cell can transform into a new blood-vessel-forming cell, called an endothelial cell, under the influence of a novel gene called pleiotrophin. -

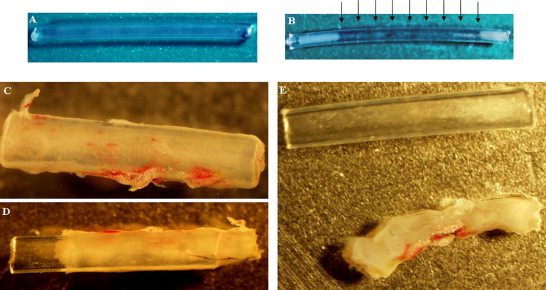

2009: SUCCESSFUL ENGINEERING OF A NEW BLOOD VESSSEL FOR BYPASS GRAFTING

Along with colleague Behrooz Sharifi, PhD, successfully engineers a new blood vessel for bypass grafting in mice using the mouse peritoneal cavity and discovers the presence of stem-cell-like cells in the mouse peritoneal cavity. -

2010: DISCOVERY OF THE FIRST-EVER BLOOD-PRESSURE-LOWERING EFFECTS OF A PEPTIDE VACCINE

Along with postdoctoral fellow Tomoyuki Honjo, MD, PhD, and KY Chyu, MD, discovers the first-ever blood-pressure-lowering effects of a peptide vaccine; the same vaccine reduced the risk of aneurysm rupture in mice. This work led to Dr. Honjo’s selection as a finalist for the American Heart Association’s Young Investigator Award as well as a Young Japanese Investigator Award. -

2012: APO A-1 MILANO GENE TRANSFER REVERSES & SHRINKS EXISTING CHOLESTEROL PLAQUE

In collaboration with his team, shows that Apo A-1 Milano gene transfer rapidly reverses and shrinks existing cholesterol plaque in the arteries of experimental animals -

2013: APO A-1 MILANO GENE TRANSFER DISCOVERED TO POTENTIALLY HELP ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Along with research team, and in collaboration with neuroscientists, shows that Apo A-1 Milano gene transfer from an IV injection can target the brain with the potential to help Alzheimer’s disease. Also, participates in a study in humans that led to FDA approval of a major new non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug, Lomitapide.